By virtue of education and occupation, I now spend a lot of time in a world that is a couple of social echelons above that of my childhood. In contrast to the blue-collar, middle-class environment that defined my neighborhood and public education, our son graduated from a private school where the annual tuition would be enough to buy a new car every year. He now attends an elite, Northern liberal arts college where the families of half the students can afford the $65,000 per year cost of attendance, out of pocket, without financial aid.

Over a decade of social overlap with members of the “one percent” has taught me more than a few lessons about class differences, and has occasionally made me self-conscious of our solidly middle-class income and home. Comments like, “Our nanny has an apartment that’s bigger than your whole house,” and “You don’t make enough money to understand why I vote Republican,” have had the cumulative effect of reminding me that our family’s definition of wealth and prosperity is out of step with the one used by wealthy elites. In fact, there have been moments of jarring collision between the working-class values that shaped me and the lives led by those in the upper class.

None stands in more stark relief for me than the Spring concert when our son was in elementary school. The auditorium, which could comfortably seat 300 people, was packed with parents and grandparents who listened intently as their cherubic progeny sang their hearts out. For the final performance, the music director asked everyone who had ever served in the military to stand. The school’s founder, a retired Navy Commander in his late eighties, was at the front, bracing the American flag. I stood, as did two other parents. One was a Coast Guard officer, the other an Army officer. I was was the only NCO. The other two men were in or near their fifties, I was in my early thirties.

It was a vivid, visual reminder that the social tier that produces our political and cultural leaders is not the social tier that places its life on the line to defend the policies they put in place. Over 300 people – physicians, attorneys, politicians, academics, corporate executives – were gathered in that room. The question was asked who there had taken an oath to serve their country. Fewer than 1 percent stood, and only one of them was an enlisted person, a former soldier who was also the only one under fifty.

The author, at left, as a newly-minted paratrooper studying at the Defense Language Institute (1993)

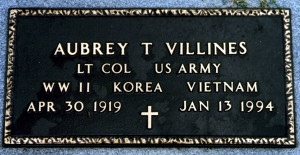

Larger samples of age and demographic data also support that anecdotal visual. This trend is reflected in the makeup of Congress, a statistic that likely includes very few former NCO’s or junior enlisted. The numbers also show that military service tends to run in families, as it does in mine (including my grandfather, a mustang who climbed from private to Lieutenant Colonel and served in WW2, Korea, and Vietnam). Increasingly, however, those are not the families that are casting the votes – in Congress or in the shareholder meetings that actually govern our country – that send us to war.

Wanting our leaders to have “skin in the game” is reason enough to encourage our elites to consider military service, but I don’t think it should be our primary motivation. Those with power will always have ways to keep their families out of harms way. I think the formative aspect of military service is a much better argument for military service among the ruling class.

Another anecdote from observing my son’s academic world is perhaps relevant here. I had the opportunity to sit in on a class at our son’s top-notch school. A gifted professor was leading a spirited discussion on the Stanzaic Morte Arthur, a medieval text that, among other things, deals with the price of honor and loyalty to friends and family. The professor asked the students, “Is there such a thing as too much honor?” One student answered, “These days, probably. Then, no.” There were murmurs of assent from the other students in the class.

It occurred to me that the students, all of whom were obviously smart, thoughtful, and conscious of the many social and political nuances and relevancies of this 700-year-old text, are likely to choose careers where concepts like “honor” and “loyalty” are considered anachronisms. They are unlikely to enter career paths where commitment to integrity and an established code might mean life or death for themselves and for their comrades-in-arms. Whether a member of the military ever sees combat (and, unlike my grandfather, I never did), joining into the centuries of tradition that train our warfighters shapes us in ways that no other experience can. To a servicemember, there is no such thing as too much honor, and there is no price too high to pay for the sake of loyalty.

The military has a long, successful history of inculcating the importance of those archaic values. It carries forward other anachronisms too, like honoring the generations who preceded us, and respect for those who have earned their place of leadership or authority through diligence, skill, and sacrifice. My own understanding of leadership was shaped as much by knowing I could trust that my NCO’s and officers earned their place, and that they would put my needs above theirs, as it was by the sophisticated, formal leadership training I received. Having watched the world of elite education firsthand, I am deeply concerned that we are training our future leaders to begin at the top and only periodically peer down from there, a critique that William Deresiewicz articulates beautifully in his book Excellent Sheep. Military service, even for those who begin as officers without having been enlisted, teaches leadership from the bottom up. Living that out changed the way I understood my obligations and expectations as a leader in ways that I think are unique to the military.

That life also let me to shared experiences of collaboration and interdependence with people from the widest range of socio-economic backgrounds I have ever encountered in one place. As an enlisted person, I served alongside a (fellow enlisted) Harvard graduate with a law degree from Boston College, as well as a soldier from the swamps of Louisiana fresh out of high school. In Basic Training, I was one bunk over from a soldier from the south side of Chicago, and one bunk over from him was a guy who enlisted after finishing his Master’s at Tuskegee. In an era where our neighborhoods are increasingly segregated by class and income, and where social mobility is, at best, stagnant, military service is a rare opportunity to actually work alongside people from a diverse range of backgrounds.

My grandfather, Aubrey T. Villines, Sr., newly graduated from OCS, stands with his grandfather, John Castner Villines, and his newborn daughter, Barbara.

“Alongside” is the key adverb there. Military service means knowing, trusting, and sacrificing for the person on either side of you, no matter how much or how little you might have in common. This is vastly different from the controlled, scripted opportunities for “cross-cultural understanding” or “community service” through which young elites are dutifully filtered before returning to their lives of privilege. I remember the moment in Basic Training when I realized that my strong academic skills and linguistic facility had absolutely zero likelihood of determining my success, and that I needed to rely on the people around me, people with far less experience with the skills that – until then – had defined “achievement” for me, to survive. When I was going through PLDC in the Okefenokee swamp in July, I didn’t care if the guy pouring his canteen of water over my head to stop me from puking had read Chaucer. I was just glad to know that if I needed him to, he would carry me out of that godforsaken swamp, or die trying.

We do our best to teach our future leaders that they should value everyone equally, but that equality takes on an entirely different dimension when you realize that the “value” of the person who is saving you from heat exhaustion has nothing to do with their level of education or tax bracket. Our next generation of leaders could benefit greatly from that kind of education.

If they are not going to get it through the military, then we need to have a serious discussion about where they might. There are millions of people for whom honor, sacrifice, and loyalty are not abstract concepts. Our future leaders should be among them.