In the eighth chapter of Mark, Jesus is finally revealed to be the “Messiah,” one anointed by the Creator to change the world on behalf of the created. Jesus immediately explains to his followers that being the anointed one of God means he will suffer rejection and pain to the point of death. When Peter is horrified, Jesus explains that his friend is looking at the moment of Jesus’ execution from a human perspective, not a divine one. To help him understand, Jesus gathers the whole crowd and explains that life is more than our physical existence, and that if we live for the things that are eternal – rather than the transitory distractions of everyday life – we will truly live, forever. “For what will it profit them to gain the whole world and forfeit their life?”

Shortly thereafter, a voice from above reveals Jesus to be more than simply one of the anointed ones, the messiahs who – throughout history – have rescued humanity at God’s behest. We hear, “This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!” Again Jesus is quick to clarify, “The Son of Humanity will be betrayed into human hands, and they will kill him, and after three days he will arise.”

Twice Jesus is proclaimed by others as one set apart by God, and twice Jesus speaks up to make clear that this does not mean glory, power, and respect – it means betrayal, torture, and execution. To be the Child of God and the child of humanity, both, means to be stretched out on the altar of human fear, weakness, and greed. Living at the intersection between divine truth and human experience, Jesus’ path has only one possible destination: the grave.

In response, Jesus’ closest friends, those who were tasked with establishing his Church and passing on his teachings to subsequent generations, “did not understand what he was saying and were afraid to ask him.”

Not much has changed in the two millennia since. We are still confused and afraid of the idea that even the Son of God, that especially the Son of God, would be the victim of all of the worst elements of what it means to be human. Over the course of history we have, in our fear and embarrassment, offered many explanations in the hope of applying some sort of logic to the incomprehensible death of God in human form. We have argued that only the blood of the Messiah could ransom us back from the devil who had made us his vassals. We have portrayed Jesus as a benevolent Lord who stepped in to pay the lengthy bill we have racked up against God, each itemized value representing the sum total of our failures on earth. We have even depicted Jesus as a willing sacrifice before a God who demands the blood of an innocent in propitiation for our multitude of sins.

Although superficially satisfying, none of these rationalizations stands up to close scrutiny or logical analysis. None is consistent with a God whose steadfast love never ceases, and whose mercies are endless. An omnipotent God who seeks to offer mercy to sinners would surely not do so by cruelly punishing the only true innocent. Simply put, the crucifixion makes no sense.

Those whose faith relies on simple formulas to explain the mind of Almighty God will be quick to point out that it does make sense if you recognize that the reasonable and fair punishment for every single human who ever lived is eternal torment and damnation in Hell, and that only the profound love of God, literally embodied in someone punished in our stead by the concentrated power of that divine justice on the cross, could save us from the fate we all deserve.

If that is true, then we are either at the questionable mercy of a tyrannical Creator who could not devise a system that avoided the murder of innocence and the eternal torment of all creation; or we are all part of a cruel and capricious universe that punishes us and our Creator equally.

As one uncomfortable with either conclusion, I must confess that I find all of the easy explanations for the nature of the cross to be unsatisfactory. I think it is best to follow the example of Jesus’ own apostles, and recognize that in the death of Jesus there is a mystery that encompasses all our fears, and all our hopes – one we are afraid to understand.

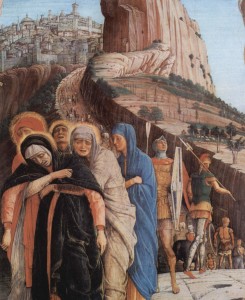

Like Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of Jesus, and the other women who gathered to watch the kind teacher and powerful prophet suffer and die, we must simply stand before the cross in horror and grief.

Our horror is the realization that we are capable of such brutality and cruelty. Our grief is in seeing in the loss of the Child of Humanity the losses that every human faces: the deaths of our loved ones, the ends of our dreams, the depredations of illness and disease, and, ultimately, our own demise. When we look into the pained eyes of Jesus, we see ourselves reflected in a mirror that shows our failings – individually and as a species – and our own pain.

It is the brutal honesty of the image in that looking glass that makes us want to find explanations of the cross that are centered on ourselves: Jesus did this for our sins; God required this for our mistakes; look how horrible we are. Maybe, though, we should look through that darkened glass and focus instead on the Jesus of the cross, not the Jesus who exists as a strawman for our guilt.

I do not mean focusing on the humanistic, secular Jesus who fought for social justice, healed this sick, fed the hungry, and cared for the poor. He is important, and we should not neglect him as part of the whole truth of the gospel, but standing at the foot of the cross is the time to ponder the divine Jesus, the holy Jesus who is – against all reason – both God and human in one wounded, bleeding, sobbing package.

Leaving aside all of our justifications and seeing only the person of Jesus, I am struck most powerfully by the inevitability of it all. As Jesus said, to his disciples in Mark 8, this is what had to happen (δεῖ in Greek, often used to indicate an obligation or an inevitable consequence). The very act of God taking on human form, of experiencing mortality, is not only death, but a brutal murder at the hands of a callous empire that places no value on human life. Jesus stepped into our lives knowing that this must happen, and did it anyway. Whatever the reason that it had to happen, the greatest miracle of the cross is that it did happen, that a God who is beyond our comprehension, our own Creator, is so drawn to us that nothing – not even the inevitability of agony and death – could hold God back from stepping into our lives.

Another miracle is that it is possible at all. For many of us, the slow slog through adulthood is one of a gradual surrender of our belief in the miraculous. We “grow up” and learn to live in the “real world,” and the myriad challenges of our mundane distractions cause us to deny the possibility that there is divine, holy, metaphysical reality beyond the one that demands that we feed our bodies and pay our mortgages. Yet at the cross we can see the collision of the world we deny with the world of our limitations. The reality of God becomes physical, not in a voice from the heavens or words carved on stone tablets, but in the lifeblood of a single person, given up freely out of love.

That leads to one more miracle of the cross. The blood that falls to the ground looks like a loss, a terrible, incalculable loss – and yet it is a victory. Every terrorist, every tyrant, every abuser has claimed their power through the threat of violence. They hold us hostage with the ultimate menace of their power over whether we live or die. However, as we see the shadow of the cross loom across the generations, we see that death is only defeat for those who lived their lives for the pleasures of the moment. The paradoxical miracle of the cross is that in loss is victory, in sacrifice is gain, and in death there is life. Our priorities do not need to be dictated by the standards set by others or by our own fears of loss, because real accomplishment looks nothing like what those with temporal power would have us believe.

If we focus on the person of Jesus, we see the miraculous mystery of the cross. We see love that cannot be dissuaded. We see the reality of the presence of God in our world. Finally, we see the truth that that the things that matter most in our lives are not the things that can be taken away, they are the things we can give to those we love, to those we do not know, and even to those who will follow in our footsteps. The story of the cross is not the story of our sin, it is the story of the person who represents the best of creation and the best of the Creator: the Child of Humanity and the Son of God. It is the story of the glorious and traumatic consequences of eternity’s collision with mortality. It is the ultimate story, in which all good things come to an end, and we learn that – all evidence to the contrary – endings are beginnings.