The crucifixion is the most widely-known event in the life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth, so much so that the instrument of his execution is the primary symbol for the religion established by his followers. For Christians, the moment of Jesus’ agonizing death at the hand of the Roman Empire is the central moment in history. As Frederick Buechner states in Beyond Words, “Jesus Christ is what God does, and the cross is where God did it.”

Knowing the significance of the event, however, is not the same as understanding it. Every era has produced new models for making sense of what took place at Golgotha. For early Christians, this was primarily a model of “ransom,” a concept that was replaced in the medieval era with one of “satisfaction.” For the leaders of the Protestant Reformation, a model of “substitutionary atonement” was the most logical, while more recent thought has applied a number of ideas, like the neo-orthodox one of “restoration” or the “exemplarism” first suggested by Peter Abelard.

Why so many (sometimes conflicting) theories to explain the one event that should be foundational and universal for all Christians? In part, this is simply the natural and necessary process of Christianity re-inventing itself to accommodate paradigm shifts in the culture. But there is a deeper reason. The crucifixion makes no sense.

Here is the most basic statement of the cross: God created a world in which the choices of that world’s inhabitants (who, like everything in that world, were created by God) forced God to brutally torture and murder the innocent and perfect, only, Son of God in the most agonizing and excruciating way possible.

What kind of god would do such a thing? On its surface, the reality of the crucifixion causes us to question either God’s kindness, God’s competence, or both. What sort of god would create a system where the only logical response to sinfulness – cruelty, selfishness, betrayal, and violence – is torture and execution of a kind, innocent man? How omnipotent can a deity be if the best world he or she can create is one in which the inhabitants will descend into a morass of self-indulgent sinfulness such that they will eventually execute the Son of God? To top it off – despite the divine sacrifice – the majority of them will still reject the offer of salvation and perish into eternal damnation.

Most Christians overlook these factors by focusing instead on the tremendous love God must feel toward humanity to be willing to offer up Jesus (and be offered up in the person of Jesus – Trinitarian doctrine is immune to logical contradiction) for the sake of humanity. They address any other logical inconsistencies with the doctrine of “free will” – humans were given the option to choose (or not) the sinfulness that ultimately led to the necessity of Jesus’ execution.

The problem with the doctrine of free will is that it only makes sense if you want to believe you’re one of the people who “chose” the right side, and can therefore be justifiably smug about your choices. Couldn’t a God who knows anything and can do anything have created a world in which everyone would have the experiences and information necessary to make good choices? If so, and God did not, then we are dealing with a cruel god indeed. If not, then God’s power and/or knowledge are seriously questionable.

These are not new questions, and both theologians and philosophers have pondered them – since the dawn of the Enlightenment – through the academic questions of “theodicy.” The classic, modern work on the subject remains John Hick’s Evil and the God of Love, and those wishing to explore these ideas comprehensively might also want to look at The Problem of Evil edited by Marilyn McCord Adams and Robert Merrihew Adams. It would be impossible even to summarize all of the different approaches to theodicy here, much less to resolve them.

So why bring them up at all? For two reasons. First, to point out to my fellow Christians – who are accustomed to taking the necessity of the crucifixion for granted – that the very idea of torturing and executing an innocent (for any reason, even the salvation of the world) is deeply problematic. Secondly, to point out to those outside the Church that Christians are – and have been for some time – keenly aware of the apparently nonsensical incongruity of a loving god who demands the cruel and brutal murder of the most perfect person to ever live before extending mercy to the rest of humanity.

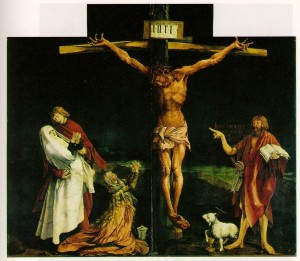

So, if at best the crucifixion is “problematic” and at worst it is “nonsensical,” why will millions of Christians around the world gather tonight in silence for a Good Friday service that – for many of us – will include the ancient tradition of “Veneration of the Cross?” If the central moment of the faith tradition defies logic, why are there still so many of us in the fold? What is the point of Good Friday if it commemorates either a god who is incompetent or one who is malicious and cruel?

We gather because the cross represents the ultimate honesty about the human experience. At the foot of the cross, seeing the suffering that even God could not escape in human form – we come face to face with the harsh reality that to live means to struggle, to face betrayal, to feel hopeless and abandoned, to suffer pain and indignity and, ultimately, to die. Most of us find effective ways to distract ourselves from the consequences of our own mortality, but on Good Friday – contemplating the agony of the Prince of Peace as he is tortured at the cruel hands of empire and greed – the vulnerability of our human lives becomes raw and tender.

But we do not venerate the cross because of some misguided masochism or morbid fascination with death and despair. Because, gathered as a community of faith, we remember – alongside the truths that we would rather forget – the unshakeable reality that we are not alone. As Paul writes, Jesus, “though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death — even death on a cross” (Philippians 2:6-8).

The message of the cross is not one of appeasement for an angry god, no matter how convenient that explanation may seem (assuming we do not stop to ponder what that really says about God). The message of the cross is companionship and compassion. We do not have a Creator who turned us loose into a violent world alone. Instead, our Creator has joined with us in the full experience of our everyday lives. No matter what the struggle, no matter how great the pain, no matter how dark or perilous the horizon – we can have the complete assurance that we are loved and supported by a present God who understands our fear and pain.

Why not instead serve a god who takes the pain away? Why not serve a god who never lets anything unpleasant happen to us? Apparently, that simply isn’t an option. The cross is also a reminder that even the only Son of God, who prayed not to face the suffering that awaited him, was exempt from the pain of human existence. For whatever reason, the world simply does not work that way.

And so, if you are seeking the cross, or seeking simply to understand why Christians seek the cross, do not approach it for fear of an angry god who demands that you accept his sacrifice or be damned for all eternity. Frankly, if the Creator of the universe is that capricious and cruel, we are all damned already. If, however, you suspect that beneath the tortures and imprecations – small and large – of everyday life, there is a source of hope and love and strength reaching out to sustain you – you are welcome to join the followers of Jesus in the shadow of one of the cruelest implements of torture ever known. It is in its shadow, the dark outline of the cross on blood-stained, that we see the arms of God spread wide to gather us in.