A Reflection for Good Friday, 2019

One of the powerful aspects of Christianity is that the liturgy and Scriptures of the Church call us to engage with history in a way that, for most of us, everyday life does not. We read of the intrigues of Mesopotamian courts, we comment on the succession of the Hasmonean dynasty, and we even describe our hope for the future in the apocalyptic fears of oppression under the Roman Empire. At our best, we do not just study these periods to mine them for theological significance. We also try to place our own circumstances in the larger scope of human experiences throughout our recorded history.

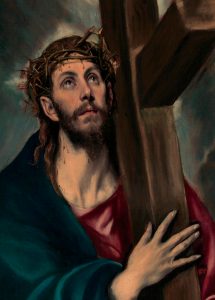

The pivotal moment of the Christian story – the crucifixion – should be no exception. It would be a gross understatement to say that Christians have written at length about the theological implications of Christ’s death. Those of us who grew up, as I did, in fundamentalist churches were reminded constantly that our sin was personally responsible. Other approaches, such as those of Peter Abelard, Karl Barth, and Gustaf Aulén take a more nuanced look at unpacking the meaning of the collision between the love of God, the perfect human, and a broken world.

I think we are best left humbled by the divine mystery of the crucifixion rather than trying to impose human logic on the unfathomable mind of God. That does not mean that we should ignore the theological implications of the death of the Son of God, but rather that we should not reduce it to some simple formula of substitutionary atonement or ransom.

Nor should we ignore the human element of the story. Biblical scholarship of the past few decades has looked beyond theology to the mundane elements of the execution of Jesus: a popular, counter-cultural, pacifist teacher who was murdered unjustly at the hands of religious fundamentalists and a cynically self-serving empire. The social, economic, and political issues surrounding the threat posed by Jesus and the early Church, and the brutality with which the forces in power attempted to extinguish that threat, are as relevant now as they were when Jesus’ brother James took over the leadership of the movement.

At that time, crucifixion was not an uncommon tool for punishing criminals and political dissidents. The Pax Romana was not only built on good roads, but on the flayed backs of men, women, and children who were beaten, raped, and executed to protect the economic and military power of the Roman Empire. Far from the eyes of those living well-fed lives in the comfort of the city at the center of the known world, the laborers and conscripts who sustained that prosperity walked daily alongside the cries of the dying and the corpses of the dead, with crosses littering the roadsides of the conquered nations.

In honoring on Good Friday the unjust execution of one man, we are also reminded of the unjust murders of millions of people throughout the history of our species. The record of the rise of homo sapiens is drenched in blood, and – in seeking to follow a man who died an agonizing death alongside condemned criminals – we cannot lose sight of the others who shared his fate.

Remembering their suffering, and our capacity for unfathomable cruelty to our fellow humans, is not just about refusing to ignore the distant past, it is about confronting complicity in that violence, both by the Church, and by the modern institutions that sustain our current peace and prosperity. The irony of a movement that took the cross as our symbol and then went on to commit heinous war crimes and genocide through crusades and colonization should not be lost on us. As we venerate the Cross in Good Friday services around the world, we should allow the mystery of its presence in our midst to challenge us by how quickly we as a people went from Mary’s grief and the Apostles’ shock to joining in with the mob when the person facing the lash was not part of our own tribe.

We should also ask ourselves, “Whom are we willing to let hang from the cross today?” Who are the people whose lives are so outside our experiences, or whose ideas or ethnicity are so different from our own, or whose actions threaten our comfort so much, that we are willing to let them suffer and die? Immigrants? Muslims? Sweatshop workers? Women and queer folk living under governments that view them as “other?”

Facing these questions allows us to venerate the full duality of the Cross.

The lesson of the Cross is not just that God’s divine love is willing to bear the full force and pain of mortal existence to be reunited with us. It is also a reminder that, given the opportunity, we will blithely and callously inflict that same pain on others, as long as their identities or experiences are far-enough removed from our own that we can do so without any deep pangs of sympathy or guilt.

The Cross tells us God loves us, and that humanity at its best – in the person of Jesus – will die for its worst enemies hoping to save them. The cross also tells us that humanity at its worst will always pick up the hammer to drive in another nail.

We must not see Jesus as alone on the Cross. We must see all of the other broken bodies and weeping faces we have been willing to place there alongside him. We must see not only our salvation, but our complicity in all of the systems that privilege the lives of some over the lives of others.

The story of the Cross does not end at Golgotha, but rather at an empty tomb. As we join with our fellow Christians in the pilgrimage of Holy Week toward the joy of resurrection, may we find at the foot of the Cross a moment to pause and remember that the very symbol of our faith calls us to always question the price we have allowed others to pay so that we could avoid picking up our own cross and following.