No book has influenced me more, or meant more to me, than To Kill a Mockingbird. The person of Atticus Finch significantly shaped my character, my parenting, and my sense of what it means to be a progressive, Southern man. He is my favorite fictional hero, above even Moses, Noah, and Job (all of whom I like a lot, for various reasons). I don’t say that lightly. I cherish the stories of our faith, and my call to proclaim them, but To Kill a Mockingbird is also scripture for me.

The “for me” is significant. I have read more sophisticated books, more eloquent books, and even more profound books. To Kill a Mockingbird, however, is the only book I have ever encountered that completely captures the South and the Southerners I know and love. Will Campbell’s Brother to a Dragonfly, Anne Rivers Siddons’ Downtown, and anything by Lewis Grizzard or Celestine Sibley all have special places in my heart for the different ways in which they tell parts of the story of what it means to be a Southerner. To Kill A Mockingbird, though, is the ethnography of my tribe.

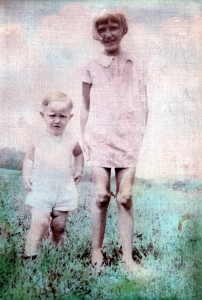

If you want to know me, you have to know my family, and if you want to know them, read To Kill a Mockingbird. My Great-Grandma Lizzie Dale Sanders Travis never left the house between Memorial and Labor Day without white gloves on. She also never had fewer than twenty people around her supper table on any given night during the Depression, because she made sure that no one she met went hungry just because times were lean. If you want to know Miss Lizzie, get to know Miss Maudie Atkinson. My Grandpa, Aubrey T. Villines, Sr. earned a law degree while fighting in three wars over 26 years, and always scored expert with his rifle qualification. Having risen from Private to Lieutenant Colonel, Grandpa Al retired from the service and then traveled both the urban and the rural South working for five different Presidents. He wanted to make sure that those without means had access to Medicaid, because he remembered what it was like to grow up dirt poor in rural Tennessee. If you want to know Colonel Villines, get to know Atticus Finch. My Grandma, Sue Travis Villines could ride a horse, milk a cow, and shoot a marble (or a basketball) as well or better than any boy on the farm. She went on to be a corporate vice president in the sixties, and she stood up for her LGBT friends when the Southern Baptist Convention turned on them like a brood of vipers. Everyone was welcome at her table, and she created a home for everyone who needed one, even those whose own people had cast them out. If you want to know Grandma Sue, then get to know Jean Louise “Scout” Finch. To Kill a Mockingbird is the story of my family.

It is also the story of my greatest fictional hero – Atticus Finch. When I was a teenager, my greatest hero – my Dad – once said to me, “Son, there are very few people in this world who – no matter what they say – you know they are always speaking the truth. Try to become that kind of man.” When I opened the covers of To Kill a Mockingbird, I met a man just like that. In a scene perfectly captured in the movie, the courtroom gallery stands as Atticus passes, and Reverend Sykes solemnly intones “Miss Jean Louise, stand up. Your father’s passin’.” It was in that moment that I finally had an iconic image of the character and integrity that I hoped would define my life. Earlier in the book, Atticus explains to his brother Jack, “When a child asks you something, answer him, for goodness’ sake. But don’t make a production of it. Children are children, but they can spot an evasion quicker than adults, and evasion simply muddles ’em.” It was there that I finally found a literary model for how I had been raised, and how I planned to raise my own child. Years later, when I stood before the judgment of a rural Southern congregation and proclaimed the good news that the gospel included LGBT people, I pictured my grandfather and Atticus standing in the great cloud of witnesses whose wreath I sought to earn. When I found myself at 3 a.m. holding a sick child, answering his questions and telling him of our love, I knew that it was also my father’s arms, my grandmother’s arms, and even the arms of Atticus Finch that held him – because I had learned how to love my son from studying their love.

There is something fetid and rotten in our culture that cannot abide virtuous icons like Atticus or my grandmother. We turn our heroes into anti-heroes. We deny their nobility and valor, claiming that we are making them more “complex” or more “real.” What we actually mean is that we have given up on the possibility of true virtue and integrity, excusing them from high standards so that we may exculpate our own lack of extraordinary moral character. Dethroning our heroes is a way to absolve ourselves of responsibility for our willingness to settle for the petty, shallow venality of choosing comfort and expedience over anachronistic concepts like idealism and honor. If heroes cannot be real, then “reality” is a place for mediocrity.

I do not want to succumb to that pessimism. Nor will I surrender my own need for real heroes because an increasingly crass and vulgar culture does not want to see their own reflection in the mirror that saints and stalwarts hold to our failed choices. To let go of those exemplars would be to tell a lie, because even if Atticus Finch never walked the Earth, I knew his touch in the hands of those who raised me. Atticus Finch is not just an archetype to me, he’s the literary incarnation of the strong, courageous, wise, honest, loving Southern men and women who have made me who I am, and who continue to challenge me to be more. I understand why amoral publishers, eager to make a quick buck off a fickle public’s need for salacious gossip, would want Atticus Finch to be less, but I want no part in it. I don’t need to know the adolescent, first-draft sketch of man who reinforces my worst fears about my own hypocrisy. I want to know the man who reminds us of what humanity can be when we are at our best. That is the “reality” whose “complexity” is worth exploring.