Requests for Dialogue

In the days following the announcement of the Obergefell v. Hodges decision, I noticed that the initial, overwhelming jubilation among my social media friends was tempered slightly by a few folks – some of whom apparently opposed marriage equality – asking that folks be respectful in their celebration, and perhaps even seek dialogue with “the other side.” I suspect that in newsfeeds where the ratio of progressives to conservatives was reversed, there was a few soft voices asking the same of their conservative friends who were screaming about the end of civilization.

One of the more articulate requests for honest conversation came from the Rev. Tish Harrison Warren, a priest of the Anglican Church in North America (a religious body that opposes marriage equality). Although my own bias is to think that the Reverend Warren is far too generous toward the concerns of the opponents of marriage equality, I do think she makes a sound point in reminding us that, “‘Dialogue’ is not a code word for ‘convincing the person you’re talking to that they are wrong and you are right.’” If we are to understand each other, and ideally maintain or even deepen our connections to each other, we must listen for understanding rather than speak for persuasion.

This is good advice, and I’ve been trying to do just that. I’ve been tremendously grateful to some of my friends who, amidst their disappointment with the Court’s verdict, have been willing to patiently and clearly articulate their experiences and perspectives for me. Allow me to go on record now as saying that some of the people, whom I know personally, who oppose marriage equality are good, kind, thoughtful people, and they have wrestled with this issue in a number of intentional ways. Of course, as with all human experience, their perspectives are not homogenous, but there are some common threads.

A Proposal for a Metaphor, in Two Parts, with Caveats

With that in mind, I have been trying to come up with a metaphor that might help those of us who supported marriage equality to hear what those Christian conservatives who opposed it are saying, and vice versa. I have ruled out any metaphor that is internal to Christianity or American politics, because I think we are only going to hear that with our own biases. The best I can come up with is a hypothetical law in a hypothetical, predominantly Muslim country, and the experience of a hypothetical Muslim woman in that country. I am cognizant, and deeply apologetic, for committing the sin of appropriation in speaking of a tradition that is not my own, but in this case I think it’s necessary because drawing in the “other” appears to me to be the only way to distance ourselves from visceral responses to familiar scenarios. I suspect that Christian social conservatives might be more skeptical of uniquely Muslim piety than they are of its Christian forms, and I suspect that my progressive friends might be more inclined to sympathize with pietism from a non-Christian religious tradition. I am not trying to speak as a Muslim, but instead trying to ask how we as outsiders might hear this hypothetical story of Muslim experience.

What I propose to do is to offer the metaphor in two parts. In the first part, I will attempt to clarify for opponents of marriage equality how those of us who support it hear their words. Obviously I am not speaking for all of us, but I think that, after nearly twenty years in this movement, I can speak from my own experience with some assurance that it represents how many of us think about the issue. Having addressed that, I will then continue the metaphor, and describe how it has been helpful to me in my goal of hearing and connecting with the hurt, anger, and confusion voiced by my friends who oppose marriage equality. In this second section, I do not intend to speak for the opponents of marriage equality. Instead, I hope to speak to my fellow supporters about my own approach to establishing a frame of reference for dialogue with those on the other side.

A Metaphor for How We Hear Our Opponents

With these caveats established, imagine that you open a newspaper from a hypothetical Muslim country, and it reads:

The High Court has ruled today that all women have the constitutional right to appear in public without wearing the hijab or even a headscarf. In a narrow 5-4 vote, the majority opinion concluded that placing separate obligations on women because of their biological sex violated their constitutional right to equal treatment under the law, and that, “while individual conscience or religious faith might compel a woman to wear the veil, it is not the role of the government to impose religious obligations on its citizenry.”

A spokeswoman for the Family Association for Women was quick to decry the ruling, stating, “This decision represents the destruction of the very fabric of our society. It bodes calamity for our nation, a terrifying future for our women, and the inevitable ruin of the families who form the bedrock of our nation. Since time immemorial, the unchanging obligation of a civilized society has been to honor and protect the modesty of our women. This is judicial activism at its worst, fundamentally reinventing the role of women in our homes, in our workplaces, and in our families. Soon we will reap the consequences, and the real victims will be our sisters, daughters, and wives whose trust we have betrayed in our rush to redefine their role.”

I suspect that, if you are a conservative, evangelical, Christian who opposed marriage equality, you are already coming up with reasons why the issue of same-sex marriage is qualitatively different. Don’t! This part of the metaphor is not about how you perceive the issue, it’s how those of us who support marriage equality see it. If you want to understand our response, both to the Supreme Court decision and to your posts, please try to understand why these issues are exactly the same in our eyes.

First, and most fundamentally, both issues are about denying civil rights. When we changed our Facebook profile pictures and shared exuberant posts of celebration, we were celebrating our neighbors’ freedom to finally live as equals, after having lived for centuries in a legal system that treated them as second-class citizens simply because of an outdated distinction of biology. To us, denying two consenting, unrelated adults the right to marry because of their sex is as absurd and untenable as denying them the right to marry because of their ethnicity, or insisting that they wear a particular article of clothing because of their sex.

There is no ambiguity or grey area here for us, because it is the logical extension of extending full status to women in our culture. Amanda Marcotte explains this extremely well. Simply put, the arguments against marriage equality were predicated on assumptions about sex and gender identity that were already archaic in the twentieth century, and which have no place in the twenty-first. Some religious groups still haven’t caught up on the issue of gender equality, thus it is hardly surprising that the two largest Christian denominations advocating against marriage equality also do not allow women to serve as pastors/priests. The conflict, therefore, is not just about marriage. At the heart of the debate is our desire to push back against certain groups’ anachronistic and irrational need to categorize and limit people based on their biological sex. For us, that debate is long-settled, and opposing it in the public square sounds to us sounds like an attempt to turn back the clock to the medieval era.

In fact, we realize that there isn’t a cogent argument for doing so, other than from religious fundamentalism. I know from past experience that opponents of marriage equality often object to the “fundamentalist” label, but those who make those objections would be well-advised to read the conclusions of the Fundamentalism Project, led by Martin Marty. Fundamentalism emerged in the early twentieth century as a reaction to modernism, when certain superstitions and prejudices could not withstand the cultural consensus created by social and scientific progress. When religious “conservatives” enter into the public sphere to deny rights to women, people of color, members of minority religions, or LGBT folks, it is fundamentalism at work.

Simply put, we do not want a theocracy, and we definitely do not want fundamentalism – Christian, Jewish, or Muslim – to dictate any aspect of our governmental policy, ever. If you self-identify as a “conservative Christian” and oppose marriage equality, please understand that we hear your rhetoric in exactly the same way that you would hear the words of an imam proclaiming that the law should require that all women – regardless of their own beliefs – wear the hijab. This is not because all supporters of marriage equality are atheists or hostile to Christianity. Many of us are Christians ourselves, and I am a theologically conservative Christian clergyman. We are not opposed to you imposing the restrictions of fundamentalism on yourself. We may not like it, but if someone believes God does not want them to marry someone of the same sex, we respect their right to choose not to do so. However, when someone acts to prevent others who do not feel the same religious obligations to nonetheless abide by them, then we feel compelled to respond.

Our response is not in opposition to personal religious belief or practice. It grows out of our strong opposition to theocracy of any kind, and our specific desire – as people who support social and scientific progress – to prevent fundamentalism from gaining any power in our government. We see the evils of fundamentalist theocracies in places like Iran and Saudi Arabia, and we recall the horrors of Calvin’s theocracy in Geneva. We do not want an America where other people’s religious beliefs are imposed on our citizens.

So, if you want to step into our shoes and hear your arguments the way we do, try to understand that it sounds to us as if you are opposing civil rights for American citizens, perpetuating a patriarchal and sexist system that defines rights and civil/family roles according to people’s biological sex, and advocating for a fundamentalist theocracy. If you want us to take your arguments seriously, you will have to address these concerns. You will have to explain how preventing same-sex couples in loving, lifelong, committed relationships from having access to the rights and protections of marriage is not denying them civil rights. You will have to explain how you are not trying to reinstate an older worldview that defines people’s social and familial roles based on their genitalia. And you will have to demonstrate that you are not trying to use your minority theological opinion to dictate U.S. law. If you can work through those concerns, if you can demonstrate that your logic is qualitatively different from those who argue that the laws of their nation should require (or continue to require) that women wear the hijab, then you will have framed it in a way that we can hear it without immediately rejecting or mocking it.

A Metaphor to Help Us Understand the Fears of Our Opponents

Now let us return to our hypothetical country.

Imagine that you are a woman named Amina who grew up in a medium-sized town in a country where the law required that women wear the hijab. You are a devout Muslim, and to you your wearing of the veil has always been a daily reminder of the comfort of your faith, as well as a public statement of your belief in the dignity and special calling of women as set apart from the coarseness of male roles and behavior.

You are well-educated, with a Master’s degree in Chemistry from a university in a nearby country. While at university, you tended to only socialize with other women who wore the hijab. In fact, you thought that, because so many women went uncovered, Muslims were a minority at your school. It never occurred to you that the women there might be equally pious Muslims, and that the hijab might not be a part of their religious practice, since going unveiled was unheard of (and in fact illegal) in your homeland. Although you encountered things in your studies that might have challenged your faith, you always resolved any contradictions you encountered by assuming that human knowledge was limited, and that God’s eternal teachings took precedence.

Now imagine that you work in a research lab at a hospital in your town. You show up for work the day of the high court’s decision, wearing your hijab as usual. You know that a couple of the staff members of the hospital are not Muslims, and you are not surprised to see that those women show up with their heads uncovered. What does surprise you is to see a significant number of your Muslim friends with their heads uncovered as well. Even more surprising is the significant number of patients who arrive throughout the day, all unveiled.

Nonetheless, the majority of the women you know well, and generally the majority of the women in your town, are still wearing the hijab. When you return home that evening to watch the news, however, you realize that the same is not true in any of the cities throughout the country. In fact, according to the television footage, the streets of the cities are packed with women laughingly marching in solidarity, their heads bare of scarf or hijab. Even more surprisingly, the reporters are only giving token attention to those who opposed allowing women to go in public unveiled, and those opponents are universally being portrayed as rural, ignorant, and superstitious. You view yourself as none of these things.

It is important for those of us who support marriage equality to realize that the shock and hurt felt by our fellow citizens in opposition is not unlike that of Amina in the metaphor above. Again, I am not trying to speak for them. Instead, I simply hope to describe how this illustration has helped me find some sympathy for their responses.

Just as our hypothetical chemist thinks that the hijab actually protects and helps women, so too do the opponents of marriage equality genuinely believe that preventing same-sex couples from getting married helps them, helps children, and helps society as a whole. Yes, I think this is nonsense, and surveys consistently indicate that the majority of Americans agree, but this is not about the logic of the argument, this is about how it feels. Opponents of marriage equality feel that they are losing a stable, healthy society in which gender roles are clearly defined, an orderly world in which people know to behave the “right” way. No matter how we may feel about that worldview, it is important that we recognize the grief and sense of loss they feel at seeing it disappear.

We must also recognize that this isn’t just about their views regarding a stable society. For them, the debate about marriage equality is also about their religious beliefs. Many, if not most, of the opponents of marriage equality view their stance as essential to their faith. This seems self-evident considering the language of the debate, but the obviousness of the fact may keep us from recognizing how deeply personal and foundational the issue has become to some people. Even though it is clear from the number of Christian denominations who support marriage equality that Christianity is not inextricably linked to opposition of same-sex marriage, some Christian leaders continue to speak as if it were. As a result, this means that some Christians hear the overwhelming support for marriage equality as an attack on their faith, as a critique of their deeply-held, lifelong convictions about God and human nature. From my perspective, this means that more work needs to be done to extricate Christianity from fundamentalism, but that work will never even begin if we cannot find honest sympathy for those who feel as if the very basis of faith is being threatened.

For many “social conservatives,” the Supreme Court’s decision not only seems like a challenge to their religious beliefs, it’s also a stunning blow to their long-held assumptions about their political power. Russell Moore, president of the fundamentalist Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, states that marriage equality opponents, “assumed that we would always represent a majority in American opinion.” Many of us are surprised to learn that they thought this way, but only because it is easy to stand in our own echo chamber and forget that our opponents live in one as well. Like our hypothetical friend Amina, many opponents of marriage equality genuinely thought that they were in the majority in their home country. The harsh realization that they are not carries with it the double blow of finding themselves in the minority, and of learning that their organizations do not carry the political power they thought they had.

Consequently, opponents of marriage equality have abruptly learned that they are members of a minority group, one with limited political clout, one with minimal and biased representation in the media. As a result they now fear the possibility of social stigma, ostracism, and even persecution over something that they view as fundamental to their identity. The irony of this circumstance is not lost on me, but as someone who has spent his professional ministerial career advocating for those who found themselves on the margins, I can also sympathize with their feelings of marginalization and powerlessness. Fundamentalists have always used a disingenuous persecution complex to further their agenda, and years of that rhetoric have now collided with the realization that their views are clearly in the minority, leading to tremendous anxiety about the possible loss of their freedom as a result of their marginal political and social status.

In light of the protections of the First Amendment, those fears are absurd, but I can understand how the tone of public opinion might engender that anxiety. Speaking for myself along, I have to confess that I want opponents of marriage equality on the margins, and I do not want them to have political power. Nonetheless, they do have a right to be heard, and if I want to hear their voices, the voices of humans speaking from their flawed experiences just as I speak from mine, it is essential that I recognize the fear and loss associated with their new-found minority status. Even if I find many of their hyperbolic claims ridiculous, I will never be able to have honest dialogue with them if I cannot find a way to empathize with the source of their fear.

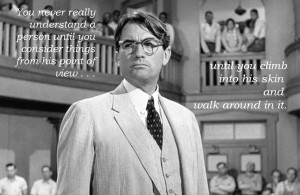

In short, as Atticus Finch said, if we are going to understand the opponents of marriage equality, we have to “climb into [their] skin and walk around in it.” We have to consider what it feels like to genuinely believe that society is in decline, and to grieve that the beliefs we hold most dear are under attack. Even as our political power as progressives seems to be on the ascent, we must remember the disquiet and frustration of feeling politically powerless. In the end, we must, without a trace of irony or sarcasm, recognize that – regardless of how ignoble and intolerant the reason – our opponents are now entering into the experiences of marginalization and stigmatization long felt by members of the LGBT community. If the late Reverend Will Campbell, a passionate advocate for racial inclusiveness, was able to hear the pain and longing in the stories of klansmen, then we can do the same for those who oppose civil rights for LGBT persons.

Concluding Thoughts

Opponents of marriage equality will no doubt object to being compared to the racists of yore. Although I am aware of those objections, I also note their historic myopia. In previous generations, well-meaning people of faith used religious rhetoric to oppose the abolition of slavery, oppose women’s suffrage (even in the modern day), and to oppose integration and multi-ethnic marriages. The rhetoric is the same, and the outcome is the same. Society moves forward, and eventually the “conservative” religious rhetoric catches up. My point here has not been to defend opponents of marriage equality, or even to assert that their arguments deserve equal weight. I think the pattern of history is clear, and I think that future generations will simply group all of these issues together as representing our gradual rejection of the tyranny of medieval superstition and ancient prejudices.

In the here-and-now, however, we are faced with the reality of neighbors, colleagues, social media friends, and family members who sincerely and passionately disagree on this issue. Neither side is likely to persuade the other, but somehow we have to find a way to see ourselves the way our opponents see us, and to try and step into their world so that we might find common ground in empathy, if not in understanding.

When Jesus was asked whom we should consider our neighbor (after commanding that we should love our neighbors as ourselves) he responded with a parable that, were he to seek to offend us as much as he did his original audience, he would likely have titled “The Good Nazi” or “The Good Klansman” of instead of “The Good Samaritan.” The call of the gospel is to love even those who hate what we represent, and whose views we despise, as if they were our brother or sister. We cannot do that unless we recognize each other’s wounds, and actively work to heal them.